Stephen Miles played a critical role in saving the newly independent Tanzania from a military coup in 1964. He was Britain's Acting High Commissioner in Dar-es-Salaam when, on the night of 19 January, he received word that a section of the army had mutinied against President Nyerere. For an hour, Miles and his American counterpart were arrested by the mutineers before being released.

British warships, including the aircraft carrier Centaur, were on exercises in the Indian Ocean. Nyerere, who feared civil war, asked Miles for British assistance in putting down the rebellion. Duncan Sandys, minister in the Commonwealth Relations Office, agreed to this. Helicopters from Centaur landed marines in the army barracks the next morning and the situation was saved. Miles was awarded the CMG later that year.

Miles helped to fan the "winds of change" towards decolonisation that swept through African countries from the 1950s to the 1980s. He served in nine Commonwealth countries, more than any other diplomat of his generation, particularly those seen as hardship posts by his Foreign and Commonwealth Office colleagues.

As Britain's High Commissioner in Zambia (1974-78) he played a significant role in the negotiations that led to black majority rule in neighbouring Zimbabwe. Arriving in Lusaka in 1974, he was astonished to discover that the Rhodesian nationalist leaders Joshua Nkomo and Robert Mugabe were in the Zambian capital, having been released from prison by the Rhodesian leader Ian Smith. Miles' approach was to befriend nationalist leaders, recognising that they would soon be in power. His briefings on their thinking were welcomed in Whitehall.

In August 1975 the presidents of the "front line states" bordering Rhodesia met in a railway carriage on a bridge across the Victoria Falls to plan for Zimbabwean independence. Miles helped to facilitate the conference. It failed to produce a solution but prompted the African leaders, including President Kaunda and President Vorster of South Africa, to hand over the problem to Britain to sort out.

Miles already had a high regard for the diplomatic efforts of Foreign Secretary Jim Callaghan, and his successor Dr David Owen, who would hold negotiations with African leaders in Miles's Lusaka residency. Miles also received a large delegation led by Andrew Young, US Ambassador to the UN. Young and Owen also met in Miles' residency where, he recalled, the British press pack rushed across his rose bed, knocking over his young daughter. Constantly interrupted by Owen's entourage of 40 staff, Miles found the best time for the two men to talk privately was on a visit to Lusaka Cathedral for the Sunday service.

In October 1976 Miles was having breakfast when Joshua Nkomo, the founder of ZAPU (Zimbabwean African People's Union) arrived to say that he and Robert Mugabe of ZANU (Zimbabwean African National Union) had formed an alliance, the Patriotic Front. Miles reported this to London. A further conference in Geneva got nowhere, but Nkomo made a suggestion to a British delegate that, as the African leaders could not agree among themselves, would the British government come up with a compromise agreement? Miles and the FCO took this seriously and, according to Miles, it was the genesis of the ultimate solution.

Owen carried forward proposals with the able support of Miles, so much so that Owen wrote to him that any solution should be called the Miles-Owen plan. But time ran out for the Labour government and, when Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979, negotiations continued under Lord Carrington, culminating in talks at Lancaster House in London. Miles had a high regard for Carrington as "a real conciliator". The talks led to black majority rule on 18 April 1980 under President Robert Mugabe, who was also seen, at first, as a reconciler.

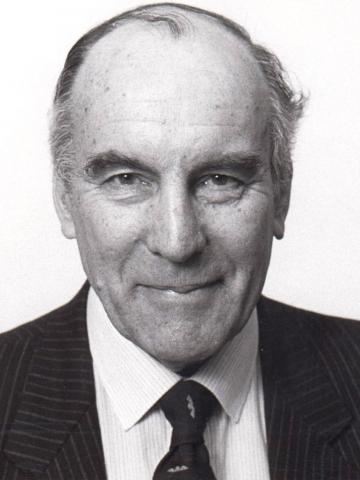

Frank Stephen Miles was born in Edinburgh in 1920. He studied history at St Andrew's University and spent four and half years as a navigator in the Fleet Air Arm during the Second World War. After the war he won a Commonwealth Fellowship to study for a Masters of Public Administration at Harvard before joining the diplomatic service in 1948.

Following posts in New Zealand (1949-52) and Pakistan (1954-57), he was appointed First Secretary in the British High Commission in Ghana (1959-62). Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and his wife stayed in the Ghanaian capital, Accra, on their way to South Africa. Macmillan made his historic and unexpected "winds of change" speech to the South African parliament on 3 February 1960, declaring that Britain would grant independence to all its African colonies and warning the apartheid regime that this would eventually affect them too.

In August 1975 the presidents of the "front line states" bordering Rhodesia met in a railway carriage on a bridge across the Victoria Falls to plan for Zimbabwean independence. Miles helped to facilitate the conference. It failed to produce a solution but prompted the African leaders, including President Kaunda and President Vorster of South Africa, to hand over the problem to Britain to sort out.

Miles already had a high regard for the diplomatic efforts of Foreign Secretary Jim Callaghan, and his successor Dr David Owen, who would hold negotiations with African leaders in Miles's Lusaka residency. Miles also received a large delegation led by Andrew Young, US Ambassador to the UN. Young and Owen also met in Miles' residency where, he recalled, the British press pack rushed across his rose bed, knocking over his young daughter. Constantly interrupted by Owen's entourage of 40 staff, Miles found the best time for the two men to talk privately was on a visit to Lusaka Cathedral for the Sunday service.

In October 1976 Miles was having breakfast when Joshua Nkomo, the founder of ZAPU (Zimbabwean African People's Union) arrived to say that he and Robert Mugabe of ZANU (Zimbabwean African National Union) had formed an alliance, the Patriotic Front. Miles reported this to London. A further conference in Geneva got nowhere, but Nkomo made a suggestion to a British delegate that, as the African leaders could not agree among themselves, would the British government come up with a compromise agreement? Miles and the FCO took this seriously and, according to Miles, it was the genesis of the ultimate solution.

Owen carried forward proposals with the able support of Miles, so much so that Owen wrote to him that any solution should be called the Miles-Owen plan. But time ran out for the Labour government and, when Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979, negotiations continued under Lord Carrington, culminating in talks at Lancaster House in London. Miles had a high regard for Carrington as "a real conciliator". The talks led to black majority rule on 18 April 1980 under President Robert Mugabe, who was also seen, at first, as a reconciler.

Frank Stephen Miles was born in Edinburgh in 1920. He studied history at St Andrew's University and spent four and half years as a navigator in the Fleet Air Arm during the Second World War. After the war he won a Commonwealth Fellowship to study for a Masters of Public Administration at Harvard before joining the diplomatic service in 1948.

Following posts in New Zealand (1949-52) and Pakistan (1954-57), he was appointed First Secretary in the British High Commission in Ghana (1959-62). Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and his wife stayed in the Ghanaian capital, Accra, on their way to South Africa. Macmillan made his historic and unexpected "winds of change" speech to the South African parliament on 3 February 1960, declaring that Britain would grant independence to all its African colonies and warning the apartheid regime that this would eventually affect them too.

Ghana had gained independence in 1957, and President Nkrumah became the host to a series of conferences for freedom fighters from other African countries, with Miles attending as an observer. Through this he got to know Nkomo, Mugabe, Muzorewa and other nationalist leaders. By the time Nkrumah was overthrown in 1966 Miles was in London as head of the West African Department in the Commonwealth Office. He was sent back to Ghana to restore diplomatic relations, severed by Nkrumah.

Miles was First Secretary in Uganda from 1962-63, taking part in its independence celebrations. The country, rich in agricultural resources, was seen as the Jewel in the Crown of Africa.

He was promoted to Deputy High Commissioner in Tanzania and was then Acting High Commissioner from 1963-64. There he met a succession of freedom fighters, including the South Africans Oliver Tambo, the President of the African National Congress, and the communist leader Jo Slovo.

"I must confess I liked them all," he recalled. "There were very few I didn't feel I could do business with and even Jo Slovo, for all his communist leanings, was actually a very enjoyable and humorous chap." Such leaders would greet Miles with bear hugs.

He was Deputy High Commissioner in Calcutta in 1970, where he had to address the threat of militant Marxist Naxalites in West Bengal. When they announced that they would assassinate a senior diplomat Miles was thought to be the most likely target. But he came to regard Calcutta as his most enjoyable posting thanks to the friendships he made with Bengalis there. His last post was as High Commissioner in Dacca, (1978-79), when Bangladesh was Britain's second largest aid recipient.

A member of the MCC, Miles played cricket at all his postings and, after retiring in 1980 he played for Limpsfield in Surrey. He was active in the local Conservatives and served on Tandridge District Council.

Frank Stephen Miles, diplomat: born Edinburgh 7 January 1920; Acting British High Commissioner, Tanzania 1964-1965; Consul-General, St Louis, Missouri 1967; Deputy High Commissioner, Calcutta 1970; High Commissioner, Zambia 1974, Bangladesh 1978; CMG 1964; married 1953 Joy Theaker (three daughters); died Oxted, Surrey 26 April 2013.

First published in The Independent, 13 June 2013