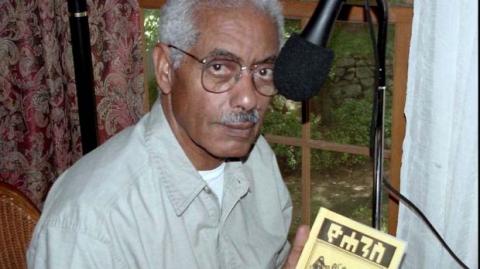

Mammo Wudneh, chairman of the Ethiopian Writers' Association, played a critical role in saving Addis Ababa, the capital city, from a bloodbath during the final throes of President Mengistu's military Marxist regime.

As liberation guerillas laid siege to the city in April 1991, Wudneh appealed to the troops loyal to the regime to lay down their arms. He urged the troops to ''sacrifice your professional pride and lay down your arms, so that we can have a better future and a chance to work out a better way for our country.''

The defending troops recognised his voice and trusted him, as he had earlier spoken out for their welfare. In response to his broadcasts that day, the troops lay down their arms and the city was saved from certain destruction and huge loss of life. In this tense situation, safe passage was arranged for the president, Mengistu Haile Mariam, out of the country.

The liberating troops in the surrounding mountains had also picked up Wudneh's broadcasts on their field radios.

Realising the danger he had put himself in from the collapsing regime, they sent in a unit ahead of the main thrust to surround his house and protect him and his family. The next day the liberation forces took over the city. Wudneh, a sincere Christian, always said that he felt he had been ''guided by God'' that day.

Mammo Wudneh was born in the heartland of Ethiopia in 1931. Following a teachers' training course in Addis, he joined the weekly Addis Zemen. In 1966 he was transferred to the then Ethiopian province of Eritrea to become head of the government's press office.

A turning point came in 1969 when he visited an international centre for reconciliation in Caux, Switzerland. Conflicts, he realised, were rooted in fear, greed and control, and he examined his own attitudes.

Returning to Eritrea, he joined an interfaith committee that aimed to build understanding between the communities.

Wudneh's change of heart was to have another unexpected consequence. Staying in an Eritrean hotel, he talked with an old Italian air force officer whom, he discovered, had been part of a raid that had strafed his village of Bashagia, during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, killing his mother and leaving him a four-year-old orphan. Enraged, Wudneh wanted to shoot the old Fascist pilot dead. Instead, praying in his room, he felt his conscience telling him: ''If you kill him, will that bring your parents and your relatives back to life?''

The next morning he went to the Italian.

''So you are the one who destroyed my village, killed my mother and left me an orphan?'' he said. Then he told the shaken man that he forgave him. The two men became friends.

During the civil war which led eventually to Eritrea's independence in 1993, Wudneh campaigned against the Ethiopian government of Emperor Haile Selassie. According to a senior Eritrean civil servant he was ''a prophet voice and spirit - a brave man who risked his life for Ethio-Eritrean relations and other unpopular issues.''

Wudneh returned to Addis in 1975, as the Marxist revolution gained hold against the backdrop of severe famine and the toppling of the emperor by military officers in 1974.

Assigned to a small office in the Ministry of Information, he wrote more than 50 books, including poetry and eight plays. He translated biographies of Churchill, Stalin, Roosevelt, Hitler, Rommel and Montgomery into Amharic.

Mammo Wudneh is survived by six children and 10 grandchildren.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 April 2012