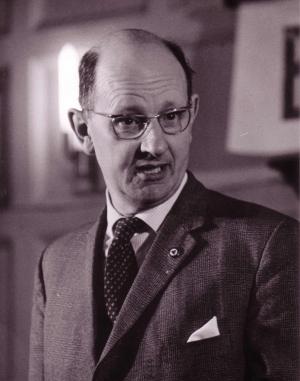

Editor for 20 years of the campaigning workers' paper 'The Industrial Pioneer'

George Walker was for 20 years editor of The Industrial Pioneer, an independent and campaigning workers’ paper which aims to hold a ‘constructive shop floor view of British industry’. An electrical and mechanical engineer by background, Walker succeeded The Industrial Pioneer’s founder and first editor, Joe Hancock, in 1963, becoming its joint Publisher and Editor until his retirement in 1983.

Hancock, a militant Liverpool docker, had launched The Waterfront Pioneer, as it was first known, as an alternative to the confrontational excesses of the hard Left. Now in its 45th year of publication, The Industrial Pioneer is known for being the moderate voice of trade unionism and claims a loyal and influential readership in 20 countries.

The paper never claimed or sought a political affiliation though its sympathies are decidedly with the Labour Party. Depending on a volunteer staff and accepting no advertising, its funding has come from its subscription readership and donations from trade union members, as well as a trust fund set up by its supporters.

Under Walker’s editorship, the paper gave extensive assessments of the annual Labour Party and TUC conferences, as well as covering the annual International Labour Organisation conferences in Geneva—an internationalist outlook continued by the paper’s current editor, Ian Maclachlan. But Walker also saw the paper as a campaigning journal, engaging through its columns in a ‘battle for the soul of Britain’. In this respect he was in the Christian Socialist tradition of Keir Hardie rather than that of Karl Marx. The paper’s emphases were always on conciliation rather than confrontation, on economic justice, including campaigning for Third World debt remission, and on the principle of ‘what is right, not who is right’.

Staff members played crucial behind-the-scenes roles in bridging differences between management and workers during the heyday of the ‘British disease’ of industrial unrest—most notably during the nationwide steel workers’ strike of 1980 which threatened the closure of the then mighty but loss-making Llanwern steelworks in south Wales.

At the time, the British Steel Corporation was losing over £1 million a day and urgently needed to implement a ‘Slimline’ package of cost cutting and redundancies, including several thousand job losses at Llanwern. But a key factor in Llanwern’s survival—when other steel mills in Consett and Corby were being closed—was a little known series of meetings, arranged by Pioneer correspondents, between steel union officials and purchasing employers. They included Gwilym Jenkins, a Llanwern branch secretary of the steel workers’ union, who had helped to organise a picket blockade of a local steel purchaser, Harold Williams. Williams was a representative of the employers’ organisation, the Confederation of British Industry, while Jenkins was a Llanwern computer operator who could see into the abyss on his screen: steel purchase orders were drying up and customers were deserting in droves.

Over a series of working dinners, Williams and other steel buyers were so impressed by the sincerity of Jenkins and his colleagues, and their determination to deliver top quality steel, that they promised to keep purchasing from Llanwern. The orders began to flow in again, and this became the basis for a remarkable turn-around at the steelworks, know in the industry as the ‘Llanwern miracle’. Today, Llanwern remains as a rolling mill, serving the nearby Port Talbot steel works.

George Walker was born in Lincolnshire, the youngest of five children of an Anglican vicar. He responded to his father’s Christian faith, a commitment which was later strengthened by his association with Frank Buchman’s 1930s Christian movement The Oxford Group. Leaving King’s School, Grantham, in 1928, Walker became a management trainee at Andrew Toledo Steel Works in Sheffield, and by the age of 24 was a director at a tooling company in Wolverhampton.

Ill health kept him from active war service, so he volunteered for a government training scheme in tool making. This was followed by eight years at the Philips Electrical’s Mitcham plant in Surrey, where he began writing for a local paper on trade union issues. After the war he spent two years in Canada as the editor of a new industrial journal there. Returning to Britain, he became an engineering craftsman and convenor of shop stewards at the Lucas Group in west London. With his industrial, trade union and editorial background he was invited to take on the editorship of The Industrial Pioneer in 1963.

He had married Gwyneth Wilson, a nurse, in 1950 and their homes, first in Acton and then Knebworth, Hertfordshire, became the focal point for the paper’s editing and production, their garage in Knebworth serving as a cut-and-paste art room in the days before desk top publishing by computer.

The Industrial Pioneer organised conference in the West Midlands, and published pamphlets and paperbacks such as Industry at its Best by Bert Reynolds, the paper’s current Publisher, and more recently my own Beyond the Bottom Line.

A passionate, ebullient figure, Walker was given to unexpected enthusiasms. He kept close links with Zimbabwe, where Gwyneth had relatives. He launched in his eighties a Trades School Foundation to give technical training to young Zimbabweans under a local manager, making use of Walker’s own intermediate technology inventions.

George Marmaduke Hollis Walker, editor and engineer, born Somerby, Lincolnshire, 31 October 1909, married Gwyneth Wilson 1950, died Knebworth, Hertfordshire, 16 July 2004.

Firs published in The Independent, 26 August 2004, and in UK Press Gazette, 3 September 2004.